Eugène Rutagarama, Conservation Advisor, and Katie Frohardt, Executive Director, heading into Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park.

This month we celebrate the third anniversary of our new chapter as Wild Earth Allies, building on decades of collaborative conservation. To mark this milestone, we interviewed our Conservation Advisor Eugène Rutagarama with whom we proudly share a long history delivering positive results for people and wildlife.

Q: You’ve played a leading role protecting mountain gorillas throughout their range and rebuilding the national park system in Rwanda following the genocide. How have these experiences shaped your work?

I think I was at a place where needs were so huge that I didn’t have any other choice than to put all of my tools into helping the broken train that was Rwanda. We were many in Rwanda, each of us trying to rebuild using our areas of expertise. The good thing is that we had unlimited energy to confront the tasks at hand and we benefited from the support of many stakeholders.

Lessons from this experience taught me that one may catalyze positive change even in extreme situations such as the post-genocide time, when people tend to lose hope. From this time, no challenge would ever impede my work towards a better future for the conservation of mountain gorillas and other wildlife species in the region.

Q: You’ve received much international recognition for your conservation work (Mr. Rutagarama is a CNN Hero and recipient of the John Paul Getty Conservation Prize and Goldman Environmental Prize). What are some lessons you’ve learned along the way?

I learned that lasting conservation comes in large part from one’s own conviction and the capacity to communicate this conviction to those influencing conservation in one way or another, for example, communities, local leaders, conservation practitioners from public agencies, NGOs, civil society, and national leaders. When a majority of these stakeholders come on board, you have a chance to succeed.

Q: You’ve known our Executive Director Katie Frohardt for a very long time – is there a story you’d like to share about how you met?

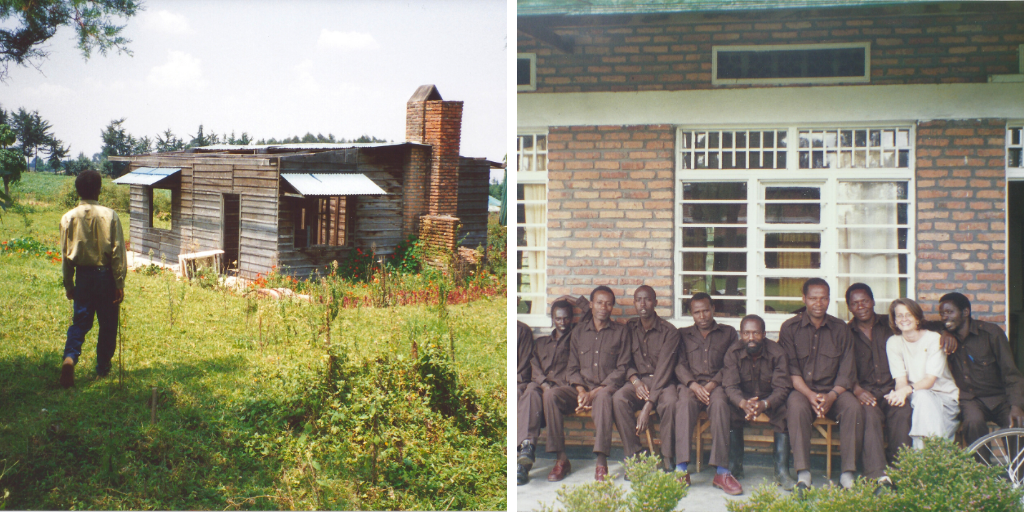

I met Katie when a lot of things were happening in Rwanda. It was just after the genocide and the country was literally on its knees. All socioeconomic sectors had fallen apart, including conservation. To address the issue of settlement of people from the diaspora, the new leadership was allocating land to returnees that had previously been protected for wildlife as part of the national park system.

When Katie and I first met, she was an advisor to the then Ministry of Resettlements and I was working for the government agency in charge of national parks. We were both focused on the changing landscape for conservation post-genocide, where land use constraints were triggering a reduction in the size of protected areas.

She came to me to share a report she had prepared in a zone close to Akagera National Park in the eastern area of Rwanda. I remember watching this young woman in her twenties asking a person she was meeting the first time to look into her report, and finding in her substantial empathy for the country and its people. I was also struck by her energy and positive thinking – much needed around me at that difficult time.

I agreed to discuss her report, a discussion in hindsight that catalyzed the course of both our careers. Our paths have crossed in positive ways ever since.

At left, Eugène (back to camera) stands in front of a field station damaged during the Rwandan genocide. At right, Katie Frohardt with Volcanoes National Park rangers in 1995.

At left, Eugène (back to camera) stands in front of a field station damaged during the Rwandan genocide. At right, Katie Frohardt with Volcanoes National Park rangers in 1995.

Q: You shared many years working in mountain gorilla conservation together – is there a particular time that stands out?

When Katie shifted her focus to land use in the northwest of Rwanda and mountain gorillas, we started working closely together. I recall one day when she proposed that we drive over 200 kilometers from Kigali to visit Gishwati Forest Reserve where the government was allocating land to returnees. As a returnee from the diaspora myself, I had a lot of sympathy for other returnees, but when I saw how the natural forest was being pulled into small pieces, I felt a wild anger.

I watched Katie try to convince the civil servant in charge to exercise restraint, but it was an uphill battle and we both returned to Kigali very frustrated. In the following months, sometimes at her own risk, Katie fought hard to ensure that the home of mountain gorilla, Volcanoes National Park, didn’t face similar treatment.

Using skilled government military officers, Katie undertook the removal of landmines left in the park by fighting forces. This project saved lives – of people working in the park and living around it, and also probably mountain gorillas.

From the time we met in 1995 until I retired in 2013, and now as the Wild Earth Allies Conservation Advisor, I have worked closely with Katie as a peer, a boss and a friend.

At left, a colonel from the Rwandan Army crouches in front of two landmines. At right, a crowd surrounds a truck that tragically hit a large landmine.

At left, a colonel from the Rwandan Army crouches in front of two landmines. At right, a crowd surrounds a truck that tragically hit a large landmine.

Q: What inspired you to become a Conservation Advisor for Wild Earth Allies? What do you think characterizes their approach to conservation?

For many years, my focus was on mountain gorillas… and luckily these efforts, combined with those of many others, saved this species from extinction. Though many species are still endangered, new challenges are occurring that threaten wildlife and global humanity at large – for example, climate change.

From the beginning, I appreciated that Wild Earth Allies chose to embrace a broad conservation scope. Having this broad view of conservation gives enough room and flexibility to intervene quickly where threats are most occurring and where there is greatest opportunity to make a difference for people and wildlife.

Q: You recently started a new project with Wild Earth Allies, focused on rainwater harvest in communities surrounding Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park – could you tell us more about this project and why it’s important?

Despite the high rate of rainfall, the region – defined by the chain of Volcanoes in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda – is well known for water scarcity due to the high penetration of water into the volcanic lava soils.

For years, communities have entered the park to fetch water for domestic use, especially during dry seasons. But fetching water in the park has also gone along with an increase of humans setting snares in the park. This poses a serious risk to gorillas, some of whom have been injured and even lost fingers or other parts of their arms and legs due to these snares.

For almost a decade, stakeholders such as the Rwanda Development Board (RDB), the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), the Greater Virunga Transboundary Cooperation (GVTC) and districts located around the Volcanoes National Parks have supported communities with water tanks, but the needs are still huge.

Unfortunately, financial support was becoming scarce so I advised Wild Earth Allies to get involved. We have helped a women-led cooperative called Imbereheza Gahunga build 50 tanks in underserved communities, and we intend to scale to 500 tanks.

We are monitoring this project closely to test our assumptions that having household water tanks will change human behavior so that those living near the park will no longer venture in to fetch water. We anticipate other benefits too, such as being able to have vegetable gardens even in the dry seasons, therefore preventing malnutrition, especially for children.

This project therefore combines conservation benefits and human wellbeing attributes, a good blend for success.

At left, Eugène speaks with members of the women-led cooperative Imbereheza Gahunga in front of a water tank. At right, Eugène outside the Imbereheza Gahunga office.

At left, Eugène speaks with members of the women-led cooperative Imbereheza Gahunga in front of a water tank. At right, Eugène outside the Imbereheza Gahunga office.

Q: Looking ahead, where do you see global conservation efforts going and what can allies do to ensure we protect our natural world?

Climate change is definitely something to watch over the next decades. Applied research of indicators, implications and subsequent actions will require global efforts, including those of Wild Earth Allies.

Q: What is an interesting fact about yourself that friends and colleagues may not know?

After I retired, I began work on a family business, a guest house called Emeraude Kivu Resort in southwestern Rwanda. We recently received very favorable ratings from the Rwanda Tourism Board and recognition as the best taxpayer in the Western Province from the Rwanda Revenue Authority.

So please come visit us and perhaps you will join me for birdwatching or for my daily swim in beautiful Lake Kivu! You may also take home a good gift made by disabled children we support or a woven basket created by the women of nearby Gihaya Island with whom we collaborate.

At left, Eugène on Lake Kivu. At right, a view of the lake from the balcony of Emeraude Kivu Resort.

At left, Eugène on Lake Kivu. At right, a view of the lake from the balcony of Emeraude Kivu Resort.

To learn more about the work Wild Earth Allies is doing in Rwanda, please visit www.wildearthallies.org. And please consider supporting our work. Donate today.