When I was a small boy, my best friend and I would go to the woods near my house and play in the jungles and forests of our imagination. My exposure to places such as Africa and Central America was through TV shows and magazines. I dreamed of thick jungles filled with animals and giant trees.

I am fortunate these childhood dreams became a career and today, I have spent over 30 years in fields of botany and ecology. My work has given me the privilege of researching and working in a wide variety of ecosystems, including more than two decades of experience in the rainforests of Belize, Central America.

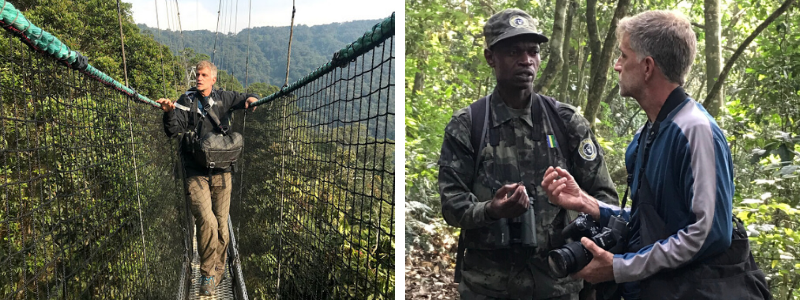

Earlier this year, I had the immense pleasure of travelling to Rwanda with Wild Earth Allies on my first trip to Africa. I was thrilled to have the opportunity to meet new conservation colleagues and experience the continent’s rich botanic landscape. Plants are my first love and I was excited to be able to visit Volcanoes National Park and its Afromontane forest to build upon my research and gain new insights.

Volcanoes National Park is part of a chain of eight major volcanoes comprising the Virunga massif. This large and compact group of mountains has formed over the Albertine rift, a tear in the earth where one African tectonic plate is pulling apart from the rest of the continent. In the space between, molten rock rises and forms volcanic mountains.

Driving from Kigali to our lodge east of Kinigi and just south of the Uganda border, in the shadow of Mount Sabyinyo, it became clear why Rwanda is the “Land of a Thousand hills.” Elevations in Rwanda are measured in the 1,000’s of meters for most of the country (roughly equivalent to 3,300 – 14,800 ft.). High elevations, ample rainfall, and an equatorial latitude makes for a cool and moist, temperate climate that averages between 15-28 °C (60’s to low 80’s °F).

It is these temperate, mountainous environments and volcanic soils that foster special types of Afromontane vegetation in which mountain gorillas are found. Afromontane forests are African equivalents of cloud forests, and like most forests they change with elevation. In the Virunga mountains, encircling the lower elevations are dense bamboo forests with stems reaching to 20 meters tall. Maneuvering off trail is difficult and slow in the bamboo, but we eventually ascended out of the bamboo zone and into the Afromontane forests I was so eager to see.

Along the trail, I was delighted to see some relatives of plants found in in the mountains of North and Central America. We found the gorillas in openings in the forest, munching on many of these familiar plants. Stinging nettles – up to our elbows and stinging us as we walked – were gathered in bunches by the gorillas, making me wince with each bite they took. They ate bedstraw, wild celery, thistle, and blackberries.

Mountain gorillas seen and photographed by Steven Brewer in Volcanoes National Park.

Mountain gorillas seen and photographed by Steven Brewer in Volcanoes National Park.

I marveled at the majestic African redwood (Hagenia abyssinica) forest and woodlands that cover the higher elevations. African redwood looks like a giant version of mountain ash, its distant, North American cousin in the Rose family.

African redwood (Hagenia abyssinica) seen and photographed by Steven Brewer.

African redwood (Hagenia abyssinica) seen and photographed by Steven Brewer.

Frequently together with African redwood, Hypericum revolutum was common. Hypericum is known to Americans as herbs and low shrubs commonly called St. John’s Wort. Hypericum revolutum is usually a large shrub in drier parts of Africa, but up here on the high, wet mountains slopes and ridges, it is a tree up to 12 meters (36 feet) tall with a trunk often over 30 cm (about a foot) diameter.

Lobelias too were tall shrubs and small trees with trunks several inches in diameter, resembling very little of the herbs back in North America. I wondered if the gorillas had created these herbaceous openings. It appeared that they were doing a good job of creating openings by their climbing and by breaking stems, and by their feeding, grabbing and pulling up and eating pounds of plants.

Certainly, the forest animals play an important role in the cycle of regeneration of the trees and other plants here. Young trees and shrubs were growing in the forest openings. Afromontane forests are special, and very rare. I hiked down feeling optimistic that these forests would persist in protected areas like Volcanoes National Park, and perhaps grow in value to the people living around them and to the global community that benefits from intact forests like these.

Dr. Steven W. Brewer is leading the Trees of Belize project in collaboration with the Environmental Research Institute at the University of Belize.

To learn more about the work Wild Earth Allies is doing in Rwanda, please visit www.wildearthallies.org. And please consider supporting our work. Donate today.