As the ProCosta team watched a transmitter-equipped hawksbill turtle turn from the open waters of the eastern Pacific Ocean back to El Salvador’s Jiquilisco Bay, they knew it was monumental. A significant discovery for science and conservation.

It was just a decade ago that hawksbills were believed to be virtually absent in the eastern Pacific. When ProCosta, our Salvadoran NGO partner-organization, helped discover hawksbill nesting grounds in Jiquilisco Bay in 2007, more than 90% of turtle nests were being poached and it was clear the recovery of hawksbills depended on successful protection of eggs and hatchlings.

Since then, ProCosta has worked with fishing communities to protect local nesting grounds and hatchlings. They are now expanding efforts to include the protection of neonate (recently hatched) hawksbills offshore, but first, they need to determine where they are.

A principal barrier to marine turtle conservation is lack of understanding where hatchlings spend their early years, commonly known as the ‘lost years’. Today, ProCosta is deploying cutting-edge satellite telemetry technology to track young hawksbills in the eastern Pacific Ocean to determine where hatchlings go after leaving their nesting beaches.

“This is an historic journey as we follow these turtles during their so called oceanic ‘lost years’, a time where very little is known about where they go, how they get there, and how long they stay before they transition to near-shore environments,” says ProCosta President, and leading hawksbill researcher, Mike Liles. “Even more intriguing is that hawksbills in the eastern Pacific behave very differently than in other regions of the world, so there is also the question of whether they even have an oceanic stage, or will they just stay close to shore or even return directly to the mangrove estuary. It is very exciting as it will help uncover more of their unique life history to guide conservation efforts.”

Currently, fewer than 700 females nest along 15,000 km of eastern Pacific coastline, with about 45% of known nesting activity occurring in El Salvador’s Jiquilisco Bay. Tracking neonates will help researchers at ProCosta locate and protect key developmental habitat – and ultimately help support the recovery of the hawksbill population in the region.

In July 2019, ProCosta launched this groundbreaking satellite tracking project with the release of four young hawksbills. The team is now collecting real-time movements of the turtles, shedding light on dispersal patterns previously unknown to researchers. Eventually, the turtles will arrive at their foraging areas – where they are presumed to remain for several years – and ProCosta can work with the Salvadoran government and fishing communities to protect these critical habitats.

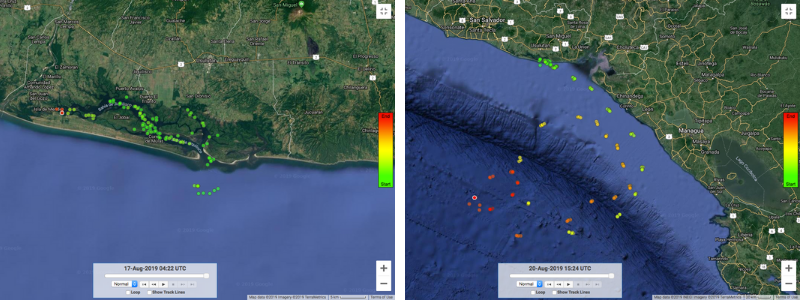

The first group, released two kilometers outside the mouth of Jiquilisco Bay on July 17th, have already begun to confirm the research team’s suspicions – divergent dispersal strategies and a potentially reduced (or non-existent) oceanic phase for some of the turtles. Even at this early stage of tracking these turtles, Liles has called the discoveries made, “monumental.”

Satellite image tracking from the first four released hawksbill on July 17th by Salvadoran NGO ProCosta. Two tagged hawksbills demonstrate divergent dispersal patterns: at left, one turtle moved into Jiquilisco Bay, and at right, another turtle began traveling towards Nicaragua.

Satellite image tracking from the first four released hawksbill on July 17th by Salvadoran NGO ProCosta. Two tagged hawksbills demonstrate divergent dispersal patterns: at left, one turtle moved into Jiquilisco Bay, and at right, another turtle began traveling towards Nicaragua.

A second group of hawksbills was released mid-August and ProCosta anticipates releasing the third and final group in the beginning of September.

This project is the first of its kind for neonate hawksbills from mangrove estuaries in the eastern Pacific and will provide critical information to help guide management and conservation actions. We are grateful to many partners who are helping make this research possible including the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Upwell, Equilibrio Azul, the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative (ICAPO), and the Salvadoran Ministry of the Environment.

Throughout this process we plan to share information, photos and satellite tracking images to help tell this incredible scientific story. For more information on hawksbills and Wild Earth Allies, please visit www.wildearthallies.org and sign-up to receive email updates.