Didiher Chacón is the Founder and Director of the Latin American Sea Turtles Association (LAST). Founded in Costa Rica in 2007, LAST works to create environments where humans and sea turtles can live together in balance.

In early 2023, Wild Earth Allies joined forces with LAST to conserve an endangered population of leatherback sea turtles. Our efforts will expand community-based conservation of two essential nesting beaches for leatherback recovery in the Northwest Atlantic.

We spoke with Didiher about the importance of leatherbacks and how we can engage coastal communities in the protection of these fascinating marine reptiles.

I first learned about the leatherback when I was a biology student in the 1980s, and it was the first turtle species I worked with in my career. It is the biggest turtle in the world at over eight feet long from head to tail. Forty years ago, I saw leatherbacks the size of a car. Today, leatherbacks that size are much more difficult to find, likely because human-caused challenges have made it more difficult for leatherbacks to live longer.

Many people believe that sea turtles are only present in the tropical areas of the world. But another unique characteristic about leatherbacks is that they migrate to cold waters in high latitudes. For example, a female leatherback can leave Costa Rica in July and swim all the way to Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada by January.

Leatherbacks control jellyfish populations, and jellyfish eat fish. And humans eat fish too. If we don’t have leatherbacks as a controller of jellyfish populations, we will have problems with the world’s fisheries.

A leatherback sea turtle (Video courtesy of LAST)

It is remarkable that a reptile is able to not only survive but thrive in these freezing waters. Leatherbacks have special adaptations for this. For example, every time leatherbacks move their front flippers, their big bodies produce heat. Living in these cold waters has a reward—they are highly productive and offer abundant jellyfish, the leatherback’s favorite food. The females can spend two years or more eating jellyfish and storing fat. Once they have gotten fat enough to reproduce every two or three years, they start their migration back to the tropical nesting beaches.

We need people to understand how important these turtles are. Leatherbacks control jellyfish populations, and jellyfish eat fish. And humans eat fish too. If we don’t have leatherbacks as a controller of jellyfish populations, we will have problems with the world’s fisheries.

What are the biggest challenges facing the Northwest Atlantic leatherback population?

Leatherbacks are a vulnerable species. In the 1990s, scientists warned about the sharp downward trend that the Eastern Pacific leatherback was experiencing. Today, this population has collapsed. Only a handful of nests are recorded on beaches where thousands of nests once occurred. The Northwestern Atlantic population is now showing similar signs of distress, and we are working to prevent the same story from repeating.

One of the biggest challenges for conserving this population is its wide distribution. They migrate long distances through nesting places in the Caribbean to northern latitudes. They even enter the Mediterranean Sea. This itself is a big challenge because it requires many countries to work together to achieve effective protection.

Another major challenge is pollution from terrestrial sources, especially plastics, because leatherbacks confuse plastic bags for jellyfish. At LAST, we have spent at least 20 years tackling this problem, but it still needs more work.

Today on some nesting beaches in Costa Rica, as many as 50% of leatherback eggs can be lost to illegal trade.

Plastic pollution on a beach in Central America (Photo by Allison Shelley)

The illegal collection of leatherback eggs for human consumption is another key problem. Today on some nesting beaches in Costa Rica, as many as 50% of leatherback eggs can be lost to illegal trade. At least 50% of Costa Rica’s coast isn’t developed. In Pacuare—one of the beaches where we work—we don’t have electricity, tap water, or a cell phone signal. It is really isolated—no roads, no bridges. No presence of authorities. And this creates a scenario where turtle eggs can be illegally collected without any control.

Sometimes, people migrate from other towns to collect turtle eggs in this area, too. The collection and consumption of eggs are not easy to eliminate from the culture, especially within areas without development and without many opportunities for jobs.

Addressing poaching requires careful approaches that balance human and conservation needs and contexts.

LAST’s field station in Pacuare (Photo courtesy of LAST)

Global warming also has a major impact on leatherbacks. The sex of a sea turtle embryo is determined by the incubation temperature. Increasing temperatures might bias sex ratios to predominantly female production. This in turn might harm the reproduction of the population. In addition, extreme temperatures are stopping the development of embryos, and we are losing a lot of the eggs on the beaches because of this. To address this problem, we are putting artificial shade in the hatcheries. We’re also putting eggs in coolers and relocating them to safer areas.

Global warming also brings sea level rise. Waters are reaching and destroying hatcheries, relocation areas, and natural nests.

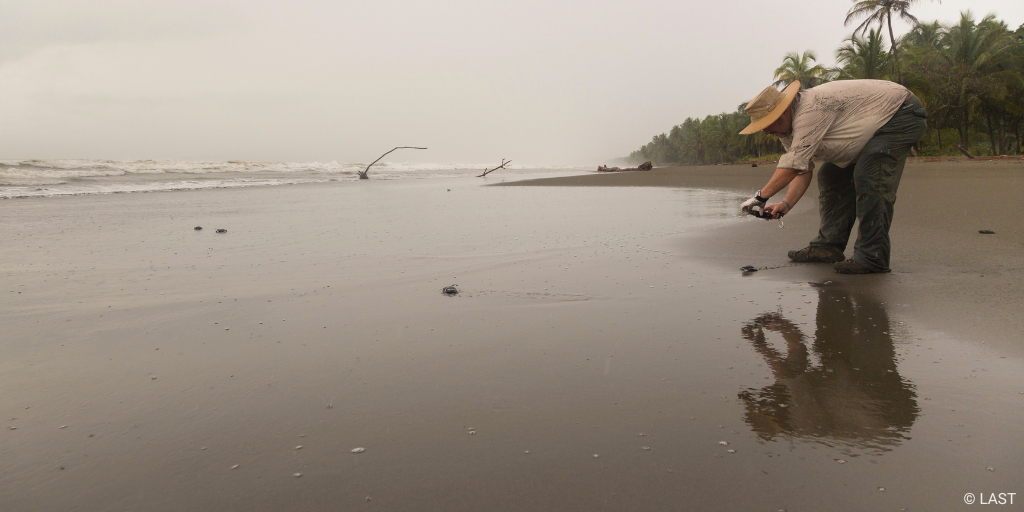

Didiher Chacón and LAST team members move leatherback eggs to a safe location. (Photo courtesy of LAST)

Global warming also brings sea level rise. Waters are reaching and destroying hatcheries, relocation areas, and natural nests. We are trying to adapt to these changes by moving the eggs to safe places, cleaning our beaches, educating communities and corporations so they reduce the use of plastics, and working to reduce bycatch.

Leatherback sea turtle hatcheries in Costa Rica (Photo courtesy of LAST)

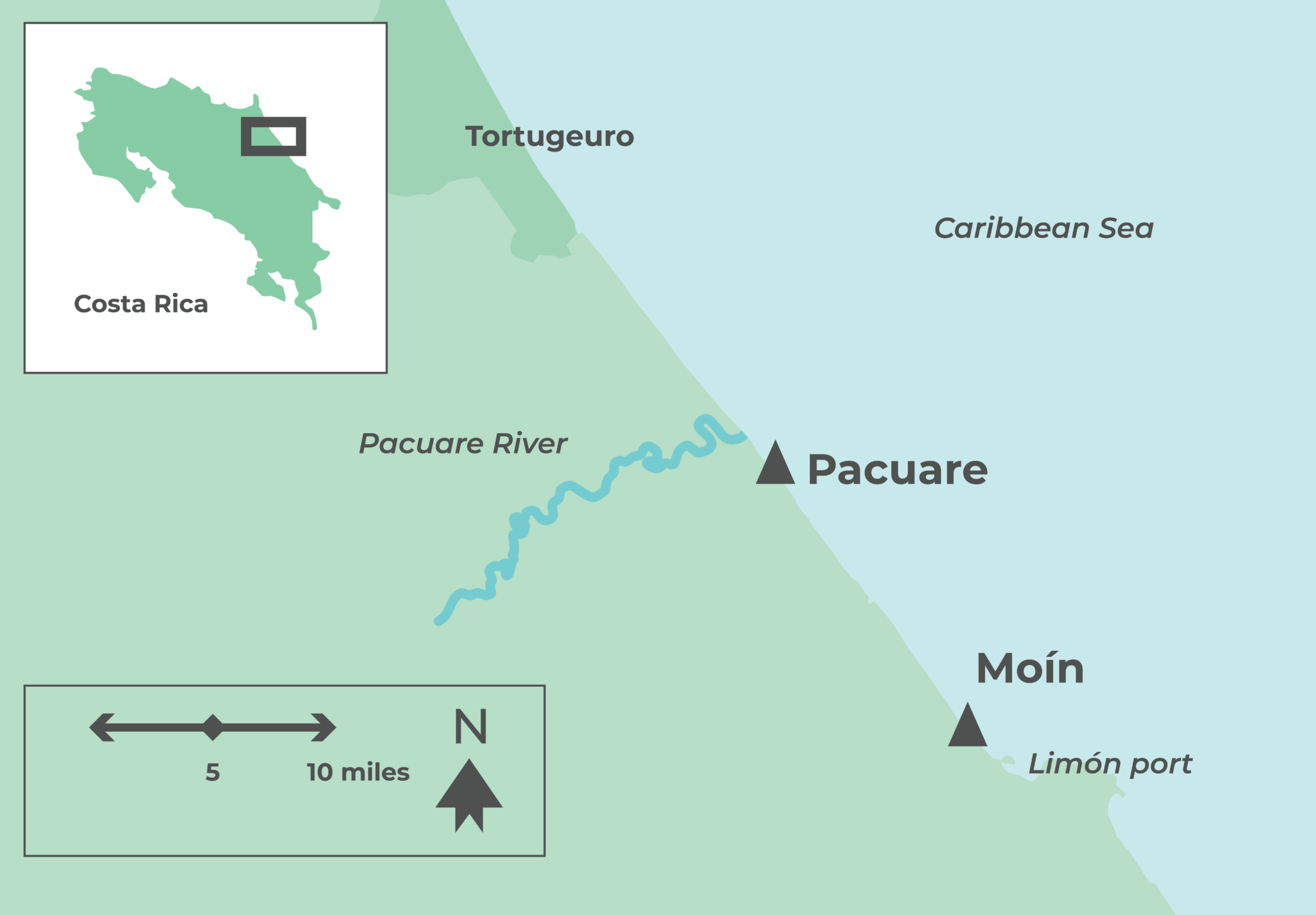

Moín and Pacuare beaches are two of the largest leatherback nesting sites in Costa Rica and the Caribbean. Moín is the main leatherback nesting area for Costa Rica, with 500–800 nests per year. Pacuare hosts 100–500 nests per year. LAST’s partnership with Wild Earth Allies will protect leatherbacks at both nesting sites.

A map showing Moín and Pacuare, the two Northwest Atlantic leatherback nesting beaches on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast

While leatherbacks tend to return to the same nesting sites, they can also shift from one to another and can even create entirely new nesting sites. In a single nesting season, a female can lay several nests through intervals of 10–12 days. In this period, a female visiting our Moín or Pacuare beaches can move and nest in other places in Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia, and beyond. We know this because we have been tagging females and researching population genetics. For example, we developed genetic studies that show Juno Beach, Florida, leatherback nesting females are genetically linked with our nesting site in Costa Rica.

We do genetic studies that prove we are now seeing daughters of the baby turtles we released in the late 1980s.

A female leatherback nests on the beach. (Photo courtesy of LAST)

The life expectancy of a leatherback is 100 years. I released a baby turtle about two nights ago, and I put it in the sand, and the turtle started to crawl into the ocean at just 2 inches long. I would need to wait 30 years for that turtle—if it survived all the threats—to come back at 6.5 feet long to lay eggs. In the sea turtle scientist community, we do genetic studies that prove we are now seeing daughters of the baby turtles we released in the late 1980s. But to see healthy population changes, I will need decades.

We have also increased education in the community. Our investment in people has had very positive results in our 30 years. For example, we brought egg collection to zero in certain community areas through the development of alternative livelihoods.

Leatherback sea turtle hatchlings (Photo courtesy of LAST)

If you fight with the government, they might close the door. Then you don’t have the opportunity to give ideas, to exchange numbers, to share reports, to be included in the decision.

So, I have learned that conservation solutions are not only about the survival of key species. They are also about solutions for people, which include economic, social, and livelihood aspects. That realization moved me to put on a tie and go talk to politicians to change minds. At the moment, I am one of the key advisors of the Costa Rican government on marine protected areas, marine policy, and sea turtles. I use the term “political biologist” as an advisor, not a fighter. When you’re an advisor, you always keep the door open. If you fight with the government, they might close the door. Then you don’t have the opportunity to give ideas, to exchange numbers, to share reports, to be included in the decision.

Volunteers release leatherback hatchlings. (Photo courtesy of LAST)

People must feel the need to be part of the solution. For that to happen, we need to show that conservation solutions work—and that the solutions produce opportunities.

If we bring volunteers and tourists to see the turtles, they can think, “I enjoy this conservation effort; I can be part of it.” And this is the point when the relationship starts.

My job for 30 years is working when everyone is sleeping in their homes. I’m working beaches from 7:00 at night to 4:00 in the morning. And this is not easy to do. You need to be filled by passion because if you are conserving sea turtles just for a salary—it doesn’t work.

And we need to create a passion in the kids. When you go to a school and talk to the kids about sea turtles, you feel their emotions grow. In 10 years, these kids will be the adults in the community. If you do the work every year, and the kids come into the hatchery and start to be local volunteers, their knowledge grows. Over the years, you have “blue” leaders who believe in saving turtles and protecting the ocean.

Local students learn about sea turtles. (Photo courtesy of LAST)

With outreach, other people might also want to be part of the solution. For example, we give presentations to companies like banana producers that create a lot of plastics. We meet with them and pass the passion and the ideas, and they might change their policies and start to reduce, recycle, and collect the plastics.

It’s very important to have some indicators of change—change of behavior, change of ideas, change of minds. And that is that the way to get people to step up and take action.

Here in Costa Rica, we work hard every night through darkness, humidity, and storms to protect leatherbacks. But then we pass on the responsibility to other societies to keep the turtles alive.

The Pacuare coast (Photo courtesy of LAST)

I am a positive person. I think we can change many things for sea turtles, but we need more help. We can reduce plastic. We can fight poaching and hunting. We can put nests in coolers and move them to cabins or hotels. We can increase the number of turtles. We need to work on all the issues facing sea turtles because it’s a complicated system.

One of the most important fights in front of us is climate change. Rising temperatures means damaging the reefs, damaging the food chain, reducing food, and increasing poverty in the local communities. We cannot only stop climate change from our beaches in Costa Rica. To win this fight, we must work together at the international, national, and local levels. This is why we need the help of the public.

A leatherback hatchling heads to the sea. (Photo courtesy of LAST)

I think it is very important for people to realize that they are totally linked to sea turtles. For example, Northwest Atlantic leatherbacks are born in Costa Rica. They have a Costa Rican passport. But when they migrate to American waters, they are Americans. And when they cross the border into Canada, they are Canadians. Here in Costa Rica, we work hard every night through darkness, humidity, and storms to protect leatherbacks. But then we pass on the responsibility to other societies to keep the turtles alive. How can they do that? By protecting them, volunteering, making donations, helping with campaigns, and participating in environmental policies. Leatherbacks are a shared resource, a shared population, which means we have a shared responsibility to protect them. I really want people to realize, “Yes, we are partners in the conservation of these turtles. We are together in this effort.”

More About Didiher Chacón

In addition to his work at LAST, Didiher Chacón currently advises the Costa Rican government on marine protected areas, marine policy, and sea turtles. He is also the Latin American Coordinator for the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST). Since 1999, Didiher has served as the scientific representative of Costa Rica in the Inter-American Sea Turtle Convention. He was also vice president of the convention’s scientific committee and the head of many working groups, including climate change, hawksbill sea turtles, and leatherback sea turtles. In 2000, Didiher represented the Costa Rican government at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). In 2005, he received the Whitley Fund for Nature Award.