Our Voices from the Field series is a behind-the-scenes look into the conservation efforts of our field teams and partners around the world. We believe preserving the planet begins with people. This series highlights talented practitioners and the work we do to protect our natural world, together.

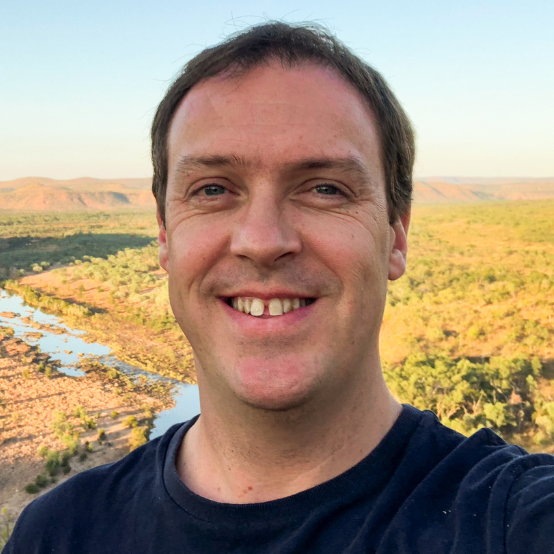

An expert biologist, Neang Thy has been exploring Cambodia’s forests for decades and has discovered several new species to science. In his role as Cambodia Conservation Manager with Wild Earth Allies, he focuses on field research and project implementation. His skilled monitoring improves protection for endangered Asian elephants, pileated gibbons, and other at-risk wildlife.

We spoke with Thy about his career path, recent highlights from his work, and his passion for wildlife.

Neang Thy (left) and Wild Earth Allies Cambodia Program Director Tuy Sereivathana patrol elephant habitat in Prey Lang Forest. (Photo by Allison Shelley)

1. Why are you passionate about wildlife, and how did this interest develop?

I grew up in a village in Kandal province surrounded by an abundance of wild animals, including leopard cats and small Indian mongoose. But my passion for wildlife came later. When I began my conservation work, I was actually fearful of certain animals. During a field expedition to the forest in Mondulkiri early in my career, I was so afraid of tigers and venomous snakes at night that I was eager to get out of the forest as soon as possible!

When I published an amphibian guide to Cambodia in 2008, my passion for wildlife really took off. I started to understand the importance of fieldwork, and I celebrated when finding an interesting or new species.

Today, my fieldwork experience is much different from my early expeditions; I am curious and motivated rather than afraid. For example, when conducting camera trapping in Prey Lang Forest, I check the footage immediately because I cannot wait to see which key wildlife species were documented.

As I travel around the forest today, I see animal habitats shrinking and remember all the wildlife around me in my childhood. This encourages me to work hard in a peaceful way to protect nature for the next generation.

Neang Thy, (right) and Tuy Sereivathana review video footage of elephants retrieved from the team’s camera traps at their field camp in Prey Lang Forest. (Photo by Allison Shelley)

2. What do you most enjoy about your work?

My favorite part of being a biologist is discovering a new species or getting good results from my fieldwork. I also enjoy publishing field data, though this can take time. I am currently preparing camera trap data for publication.

Neang Thy (left) and colleagues survey a mineral lick unearthed by elephants in Prey Lang Forest. Left to right, Thy, Local Field Lead Srey Ben, Ranger Hiv Chen, and Tuy Sereivathana. (Photo by Allison Shelley)

3. You recently conducted surveys of endangered pileated gibbons in Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary. What did a “typical” day of field research and monitoring involve?

Spending time in the forest is complex. We plan extensively to complete our mission and return with worthwhile results. A typical day of field research on pileated gibbons began the night before. We arranged all the field gear including GPS, compass, binoculars, camera, notebook, pencils, and datasheets.

We woke up early on the survey day around 4:00 a.m. and cooked, drank coffee, and packed meals. At around 5:00 a.m., each team of two people traveled up to an hour to reach their respective listening posts. When they arrived, each team sat quietly and listened to gibbon songs for several hours until around 12:00 pm.

This is when the real excitement happened. When they heard a gibbon song, the team recorded key information: the starting and ending times of the song, the bearing of the song using a compass, the estimated distance between the observers and gibbons, the sex and number of gibbons based on the songs (or sightings), as well as the recorded dates, habitat types, and location of listening posts. On this recent trip, I joined different teams each day as a monitor and advisor. I also took pictures of the gibbons.

At the end of the day, the teams returned to the camps and compared their data. We repeated these activities for three days to make sure we were able to confirm the presence or absence of each gibbon in the area. After morning surveys on the third day, the team moved to the next listening posts in the afternoon. Sometimes, this meant it was already very dark when we had to set up a new camp and get ready for the next morning.

Neang Thy and other members of the Wild Earth Allies Cambodia team captured footage of a female pileated gibbon while conducting surveys of this endangered species in Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary.

4. You have discovered new wildlife species. What is this experience like for you?

Discovering a new species is an extremely exciting activity. When I saw the bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus phnomchiensis) for the first time, I knew right away this animal had never been seen before. Other times, I thought a species in the field was new but learned in the lab that it was not.

I believe new species are always around me, and that inspires me to work hard in the field to search for them. When we find cryptic species that may look identical but vary genetically, it takes time to sort this out. It requires a review of all accessible museum specimens of different geographic ranges, molecular techniques, and statistics to separate them.

The newly discovered species of bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus phnomchiensis). (Photo by Neang Thy)

5. You have had a lot of exciting accomplishments in your work recently, like discovering new species and winning the E.O. Wilson Research Prize (awarded each year to one outstanding paper from the Journal of Natural History to recognize excellence in natural history research). Is there something you feel most proud of?

The paper describes a new species of red-eyed frog, which is one of three cryptic species within the Leptobrachium complex. When we found this in 2007, we did not expect it to be new at first because we compared it to the known species from nearby locations. In addition to studying this new frog, my co-researcher Dr. Bryan Stuart submitted the award-winning research paper out of 300 entries. I was so proud to see this first prize from my co-authorship with Dr. Stuart and others.

6. Do you have a favorite species – or one about which you feel most concerned right now?

Two species that carry my name are among my favorites: one gecko (Cnemaspis neangthyi) and one frog (Leptobrachella neangi). The gibbon is also an especially lovely animal for me.

The species I am most concerned about is the Asian elephant. I am also concerned about those species “in the corner,” meaning new species we have not discovered yet. Because of habitat changes, they may have gone—or will go—extinct without our knowing about their existence.

An endangered Asian elephant eats leaves in Cambodia. (Photo by Allison Shelley)

7. What do you wish more people knew about Cambodia and its biodiversity?

I wish more people were aware of Cambodia’s conservation importance. We need more collaboration to protect the country’s valuable natural resources that sustain our environment and human health.

The sun rises over the Mekong River, which flows just outside of the Prey Lang Forest, as seen from the village of Siem Bouk in northern Cambodia. (Photo by Allison Shelley)

8. What advice do you have for young conservation practitioners in Cambodia?

I advise our youth to never give up protecting Cambodia’s biodiversity. I urge them to stay optimistic and come together as drivers for environmental conservation. The opportunity for lasting change for people and nature is in their hands.

Girls act out a skit during a Wild Earth Allies Cambodia environmental education festival in the village of Siem Bouk. (Photo by Allison Shelley)

Learn more about our work in Cambodia, and please consider joining us by donating today.